Jessica Hankins in the Sclerochronology lab at HPU..

When it comes to pioneering coral research HPU Master of Science in Marine Science (MSMS) student Jessica Hankins has set a high bar. Her geochemical research has never been done before on these time scales. Anywhere. Hankins is using Raman spectrometry techniques to test if coral calcifying fluid saturation state has declined in corals across the tropics over the past century.

In December 2021, HPU acquired a Raman spectrometer that uses lasers to analyze coral reefs and marine debris found off Hawai‘i’s waters and on its beaches. The pioneering Raman technology provides researchers like Hankins the ability to better understand how corals are affected by climate change and to learn how corals grow and respond to ocean acidification and warming.

“Raman spectrometry is able to provide a structural fingerprint of the minerals and molecules within coral skeletons,” said Hankins. “Shifts in the frequency of the Raman laser are characteristic of disorder within the crystals that compose the coral skeleton. The amount of disorder in the crystal can be used as a proxy for the conditions from which the coral skeleton formed.

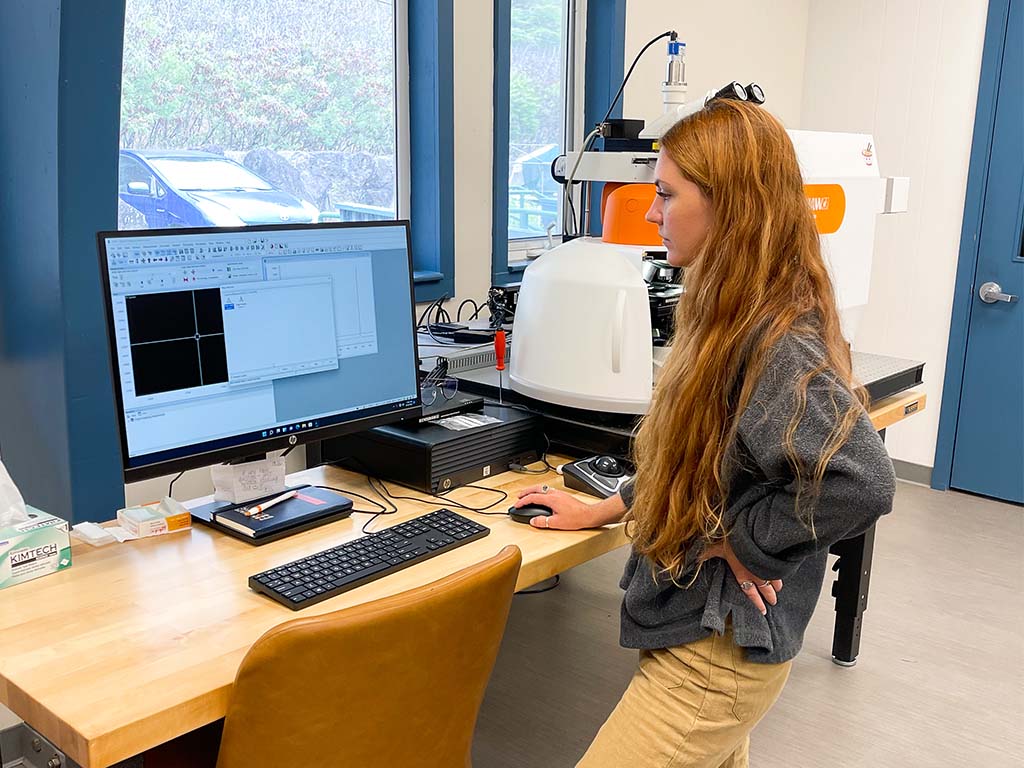

“I’m currently looking at coral cores from the Great Barrier Reef, the Coral Sea, and the Red Sea, dating to the early-nineteenth to late-nineteenth century. With the Raman spectrometer at HPU, I can quantify changes in the coral skeleton over time periods that have never been studied before.”

Jessica Hankins conducting coral research on a Raman spectrometer..

Corals construct their intricate skeletons by taking in seawater through their tissue layer into a small, isolated space between the tissue layer and existing skeleton called the coral calcifying fluid. Corals can change the chemistry of the calcifying fluid so that they can rapidly form calcium carbonate, which is then deposited on the existing skeleton to create layers of coral growth.

“The structure and chemistry of each layer of the coral skeleton varies due to changes in temperature and seawater chemistry,” said Hankins. “It is thought that with ocean acidification we will see structurally weaker and less dense coral, leaving them more susceptible to erosion, storm damage, and other environmental factors that can lead to their demise.”

Hankins was born and raised in New Jersey. She earned a B.A. in Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences from the University of Colorado Boulder where she became interested in ocean acidification research. After earning her B.A., Hankins moved to Thailand to conduct research on coral reefs, and later to Florida to continue research with the ocean acidification lab at Mote Marine Laboratory as a carbon chemist.

It was HPU Oceanography Professor Thomas DeCarlo, Ph.D., that ultimately piqued Hankins’ interest in attending HPU’s MSMS program.

Jessica Hankins stands next to a coral core..

“I’ve been following Professor DeCarlo’s research since he was a Ph.D. student at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI),” said Hankins. “He is very accomplished, and the coral research he has done with Raman is groundbreaking. I knew HPU would be the perfect place to get the experience I wanted to pursue my Ph.D. and eventually lead my own lab in a similar area of research.”

HPU provides various opportunities for undergraduate and graduate students to interact with professors, using tools they would later use in their professional careers. Professor DeCarlo’s Sclerochronology lab is interdisciplinary where students can work side-by-side on different projects.

Hankins expects to graduate from HPU with her MSMS degree in May 2023. She plans to continue her research and begin her Ph.D. in marine geochemistry next fall.

“Calcium carbonate chemistry is my main area interest,” said Hankins. “I would love to pursue a Ph.D. in this field and build on the skills and experiences I have acquired at HPU.”

To learn more about the MSMS degree at HPU click here.